Introduction to Git

Keeping track of all of the changes in your project over time is good practice. How many times have you edited something in something you were writing and then wanted to go back and see what you had in the first place? Wouldn’t it be great to know what changes you made and when you made them?

A version control system facilitates this process of keeping track of changes over time. Beyond that, it allows multiple people to collaborate and work on parts of the same project simultaneously. We will use version control extensively in class, both for collaboration among teammates, and for homework submission and grading.

There are many version control systems. The four most prominent, in order of age, oldest to youngest, are CVS, Subversion, Git, and Mercurial (the first version of Git was released about two weeks before Mercurial, so they are really the same age). Today, Git dominates.

Git was developed by Linus Torvalds, the person who developed the Linux operating system. He named Linux after himself, and he decided to also name Git after himself (“git” is British slang for a stupid person). Try typing

man git

on the command line and read what the NAME of the software is.

Using Git as a version control system allows communication with remote

repositories (“repos” for short) hosted by services such as

GitHub, GitLab or

Bitbucket. These services provide

university-affiliated people with a .edu email address with perks

that include free private repositories. We will use GitHub for this class, and you should have already set up an account.

Remote repositories are not only a great way for keeping your data safe and in the cloud. They are also an excellent tool for collaboration since Git allows multiple users to edit the shared files simultaneously and has a method to merge changes afterwards. Public repositories can also serve as a vehicle to distribute code (or other files).

You can find more information about Git here. It is well documented. Here is an excellent one-page (front-and-back) cheatsheet.

Let’s get started. You all should have a version of Git installed on your computers.

Configuring Git

We will start by configuring Git on your computer. We will do the configuration with --global

flags, which means these specifications work for all of your

repositories. First, we’ll specify the name and email address of the

person working with Git on your machine (that’s you!).

git config --global user.name "YOUR NAME"

git config --global user.email "YOUR EMAIL ADDRESS"

We will not go into merge conflicts in too much depth now, but you need to tell Git how you want to handle situations when there are edits to the same file coming from two or more different computers (could be a collaborator, or could be you on your home computer and your work computer). I generally like to use Git’s default.

git config --global pull.rebase false

Git is very well documented and help is easily available. If you need to

know more about config, for example, just enter:

git help config

Cloning Repositories

Your team’s repository is already set up and hosted on GitHub. You will

need to clone it from its URL; you will have access to that once the

teams are finalized. To practice cloning, we will clone one of the

zillions of public repositories that are hosted on GitHub. We will clone

a simple package, called insulter that will hurl Shakespearean

insults at you. Enter the following on the command line.

git clone https://gist.github.com/3165396.git insulter

Note that the insulter package is now on your local machine. You have a copy of it on your own hard drive. You do not need to be connected to the internet to use it.

Now, cd to insulter and you can start using it, thou wayward

tickle-brained flap-dragon!

python insulter.py

Pulling in changes

Actively developed repositories are constantly being updated. After you clone the repository, its authors (e.g., your teammates) may add or edit things in the repository. For you to get those changes, you need to fetch them and then merge them into what you have locally.

To fetch the updated repository, you guessed it, you do:

git fetch

The result is stored in a hidden directory, .git/FETCH_HEAD.

(Directories that begin with a . are hidden; you don’t see them when

you type ls without any flags.)

Now that there are changes, you would like to update your local repository. Provided you do not have any local edits, this is seamless. You just do

git merge FETCH_HEAD

Now your repository will be up to date.

A shortcut for the commands

git fetch

git merge FETCH_HEAD

run in succession is

git pull

In practice, you will use this a lot, but sometimes fetching and merging

can be useful. Note that git pull is actually shorthand for

git pull origin main

which is the more verbose way of saying that you want to pull the main

branch from the remote repository named origin. We will not

discuss branching in this course, but it is an important concept to

learn about.

Generally it is good practice to pull before you start working each day to make sure you pull in any updates your collaborators may have made.

Default branch name

When you create a new repository in GitHub, the default branch name is main. This was changed from master beginning in late 2020. For existing repositories created before that time, the default branch is still called master unless it is explicitly changed to main (or whatever else the developers want to change it to). Renaming master to main can cause problems in maintaining repositories, and you will find the many software packages still have the default branch named master to avoid those difficulties. This should not be a problem with any of your work in this class; I bring it up so you are aware when you see many “main” branches called master.

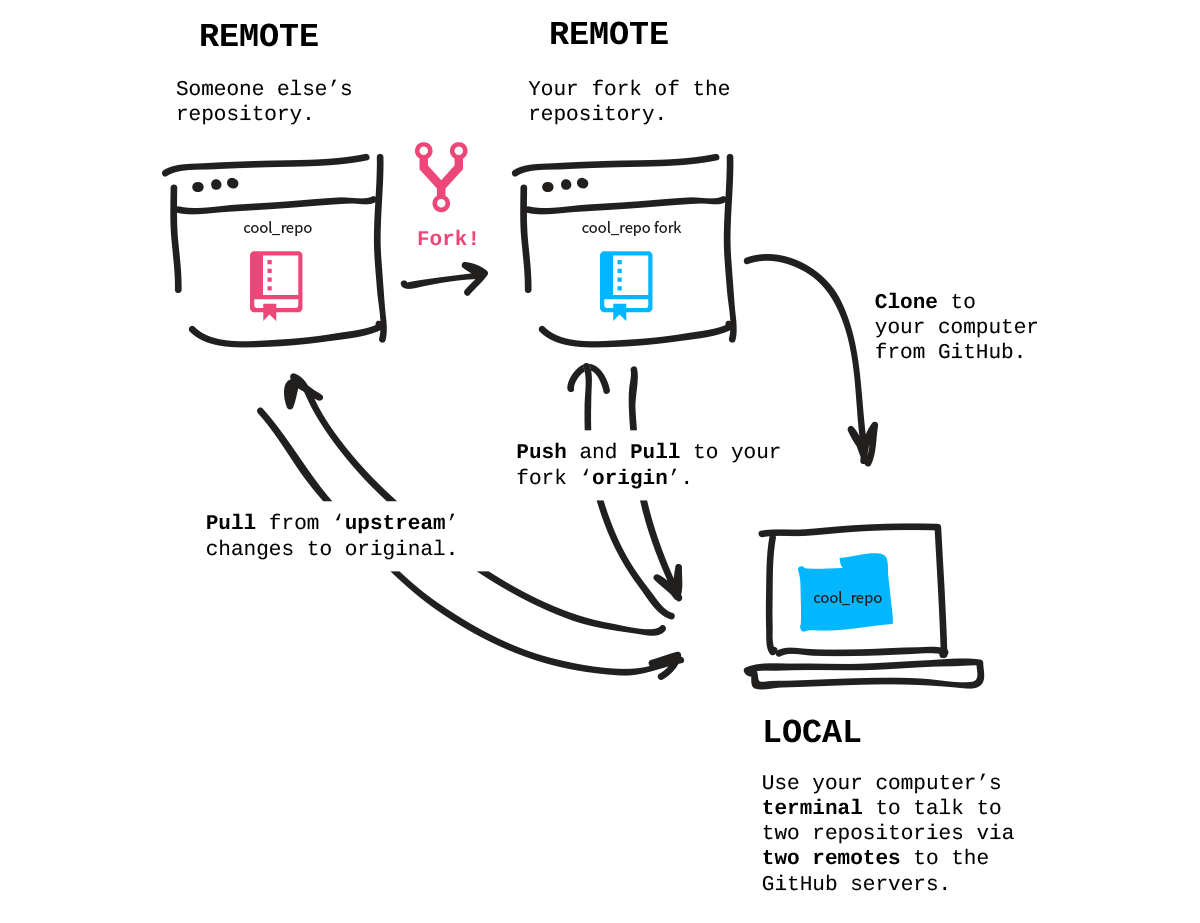

Relationships among your local machine and your repository

Let us think about how we have things set up, referring to the excellent image below from Jessica Lord. For now, focus only on the blue portions on the right (ignore forking and the upstream repository). Remotely, in our case on GitHub, lives the repository that I created for your team.

When you cloned your repository, you pulled it down from GitHub and put it on your local machine (probably your laptop). Whenever you make changes the repository, you do so on your local machine. You then add whatever files you changed to alert Git that you care about the changes and want it to keep them under version control. You then commit your changes, which tells Git to create a snapshot of exactly what the repository looked like when you did the commit. Associated with a commit is a commit message, which briefly describes what you changed on that commit. When you push your commits, they go to your team’s repository.

So, here is how the command line would look if you wanted to work on a

file called my_file.py in your repository. First, pull in any

possible updates from your teammates. Actually, let me say this more

forcefully.

Always git pull when you start working.

The first thing you do on the command line is

git pull

Now that you have an updated repository to work with, you go to work and

you edit my_file.py, let say by cleaning up some of the data

wrangling procedures. You then need to tell Git add the file.

git add my_file.py

You might want to check to make sure you didn’t have other edits you want to add to the commit. You can do this by checking the status.

git status

The result might look something like this.

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: my_file.py

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: another_file.py

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

yet_another_file.py

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

In that status report from Git, it says the you modified a file called

another_file.py that is already under version control (it has been

added and included in a commit before), but you have not added it for

this commit. If you want to add it, you would do

git add another_file.py

There is another file, yet_another_file.py that exists in the

directory that you have never added, so Git is not tracking it. You can

also add that for this commit.

git add yet_another_file.py

Now everything is ready to commit. To commit with a commit message, do the following.

git commit -m "Updated wrangling methods in my_file.py."

Git now has a snapshot of exactly what your repository looked like at the time of the commit. Now, the commit is still only on your local machine. In order for your collaborators (or the whole world, if it is a public repo) to have access to it (and in order for it to appear on GitHub), you need to ``push`` it. To do that, we do this:

git push origin main

Here, origin is a nickname for your remote repository. main is

the name of the branch we are pushing to in the GitHub repository. I.e.,

it is the main copy. (We will not really talk about branches or

branching.)

That is the basic set of operations to get your work into the repository and out to the remote for your teammates.

A note on commit messages

As just described, the -m after git commit specifies the

commit message. This is a brief bit of text that describes what has

changed in the repository. It is really important to write informative

commit messages (and here are some beautifully described rules for good

commit messages). By

contrast, most commit messages that people write are

useless.

Note that good commit messages also require that you commit often for incremental changes. Not writing good commit messages is unfortunately one of my greatest weaknesses. But it should not be yours.

What to do in case of a fire

It is important to commit and push often. It helps collaboration and protects your work. So, what do you do in case of a fire in your building?

git add *

git commit -m "Building on fire, no time for meaningful commit message."

git push origin main

git out of the building

.gitignore

Notice in the sample output of git status above, Git let us know

that there was an untracked file in the directory. Sometimes you do want

to have files in the directories of your repository, but not keep those

files under version control. Examples of these might be binary files,

large data sets, images, etc.

Fortunately, you can tell Git to ignore certain files. This is done

using a .gitignore file. Each

line of of the .gitignore file says which files to ignore. For

example, to ignore all files that end with .tif, you would include

the line

*.tif

in your .gitignore file. The * is a wildcard character which

says to ignore all files that have a file name ending with .tif,

regardless of what the prefix is. Now, whenever you you use

git status, any file ending with .tif that happens to be on your

machine within the directories containing your repository will be

ignored by Git.

Just because *.tif appears in a .gitignore file does not mean

that all .tif files will be ignored. If you explicitly add a file

to the repository, Git will keep track of it. E.g., if you did

git add myfile.tif

then myfile.tif will be under version control, even if other

.tif files laying around are not. (Note, though, that you typically

do not want to have binary files under version control. You usually only

keep code under control. Typically only data sets used to test code are

included in the repository. Version control is not really for data, but

for code.)

Finally, since it begins with a ., the .gitignore file will not show up when you

run ls at the command line without the -a flag.

You have a .gitignore file already present in the repositories I set

up for you. It is there to tell Git to ignore the files in the folder

data/.

Additional information about using Git

This lecture gives a minimal introduction about Git/GitHub that you need for this class. In recitation, the TAs will give you more tips and traps about using Git. Beyond that, there is much to learn about using Git, branching in particular. For that and much more, there are plenty of great resources on the internet. GitHub has a good series of guides to get you started.